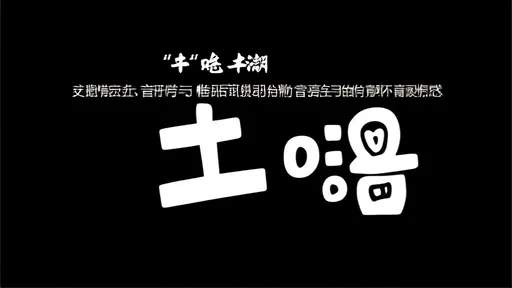

In the vast and varied landscape of global music, few phenomena are as culturally specific and instantly recognizable as what is known in China as "tu hai" music. This genre, often translated as "earthy" or "tacky" pop, evokes a strong, almost visceral reaction from listeners. For some, it’s a guilty pleasure; for others, it’s an auditory assault. But what is it, from a musicological perspective, about certain rhythms and sonic textures that makes music feel so distinctly "tu" or unsophisticated? The answer lies not in the notes themselves, but in their arrangement, their cultural context, and their deviation from established Western-centric norms of musical "quality."

The very term "tu hai" is loaded with socio-cultural meaning. "Tu" literally means "earth" or "soil," but colloquially, it implies something rustic, unsophisticated, and decidedly not urban or cosmopolitan. It’s music perceived as being from the countryside, for the countryside, untouched by the polished production values of mainstream pop capitals like Beijing, Shanghai, or Los Angeles. This perception is the first crucial layer. The feeling of "tu" is not an inherent property of the sound waves but a cultural judgment, a marker of difference from a perceived center of cultural power and taste.

From a purely rhythmic standpoint, "tu hai" music often employs patterns that are considered simplistic, repetitive, or rhythmically "square." In Western music theory, particularly in genres like jazz, funk, or even sophisticated pop, value is placed on syncopation—accenting the off-beats to create a sense of swing, groove, and complexity. This syncopation is often what musicians refer to as "feel" or "pocket." Much of "tu hai" music, by contrast, favors a relentless, four-on-the-floor beat where the kick drum hits every quarter note with unwavering consistency. This creates a driving, pulsing rhythm that is powerful and direct but can be interpreted as monotonous or lacking in nuance to ears trained on more syncopated grooves.

Furthermore, the sound palette itself contributes significantly to the "tu" aesthetic. "Tu hai" productions frequently utilize synthesized sounds from older, cheaper keyboards and drum machines. These sounds—bright, plastic-y pianos, overly crisp hi-hats, and synthetic brass stabs—are often generic presets that haven't been processed or edited with the detailed audio engineering common in high-budget productions. In modern Western pop, immense effort is spent on sound design, layering, and mixing to create a rich, deep, and "expensive"-sounding texture. The raw, unadulterated use of these basic synth tones signals a lack of this production sophistication, marking the music as amateurish or outdated, hence "tu."

Melody and harmony also play their part. The chord progressions in "tu hai" songs are often extremely simple, revolving around a few basic major chords (I, IV, V) in a loop. There is a avoidance of the more complex chord extensions (7ths, 9ths, suspended chords) or key changes that are used in other genres to create emotional depth and surprise. The melodies are often highly diatonic, sticking strictly to the notes of the scale, and are catchy in an almost childlike way. This simplicity makes the music incredibly accessible and easy to sing along to, but it also feeds the perception of it being unschooled or primitive against the benchmark of more harmonically adventurous music.

The cultural element cannot be overstated. The feeling of "tu" is deeply tied to China's rapid urbanization and the shifting cultural landscape. As millions moved from rural areas to booming megacities, a cultural dissonance emerged. The music they brought with them—or the music that remained popular in their hometowns—became a symbol of their former lives, now looked down upon by an emerging urban middle class eager to define its modernity and sophistication. "Tu hai" music, therefore, is not just sound; it's an audio symbol of a specific class and geographic origin, deemed less desirable by those seeking to align with global, metropolitan tastes.

This creates a fascinating paradox. The very elements that make it "tu" are also the source of its power and appeal. The pounding, unwavering beat is physically energizing and perfect for dancing in open squares or at rural festivals. The simple, repetitive melodies are instantly memorable. The unpretentious, low-fidelity production feels authentic and emotionally direct to its core audience, untouched by the cynicism and calculation of the mainstream music industry. In this sense, "tu hai" is a vibrant, grassroots folk music that has been digitally updated for the 21st century.

Ultimately, labeling a rhythm or a song as "tu" is an act of cultural positioning. It reveals more about the listener's own frame of reference and biases than about the music's objective qualities. The rhythms themselves are not inherently "tacky"; they are simply different from the complex polyrhythms of Afro-Cuban music or the swung grooves of American R&B that have become a globalized standard for musical "cool." The phenomenon of "tu hai" challenges our assumptions about taste and sophistication in music, reminding us that these concepts are never neutral. They are constructed within specific social, economic, and historical contexts. What sounds unsophisticated to one ear might sound like the most authentic expression of joy and community to another.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025