In the hushed listening rooms of audiophiles and the echoing halls of music production studios, a debate rages with near-religious fervor. It is a discussion that predates the internet, streaming services, and even the compact disc. The central question is deceptively simple: does vinyl sound better than digital? The answer, however, is anything but. It is a labyrinth of subjective experience, technical nuance, and deeply personal psychology, a debate destined to remain forever unresolved.

The case for vinyl is built on a foundation of warmth and character, qualities often described in the language of romance rather than science. Proponents speak of the analog soundwave, a continuous, unbroken stream of information captured in the physical grooves of a record. They argue that this continuity more faithfully reproduces the original performance, capturing subtle nuances and harmonics that are lost in the digital conversion process. The sound is often described as warmer, richer, and more organic. It has a palpable texture, a slight imperfection that lends it a human quality. This is frequently attributed to the gentle distortion introduced by the playback system itself—the faint crackle and pop, the warmth of tube amplifiers often paired with turntables. These aren't seen as flaws but as part of the aesthetic, the aural equivalent of the grain in a photograph.

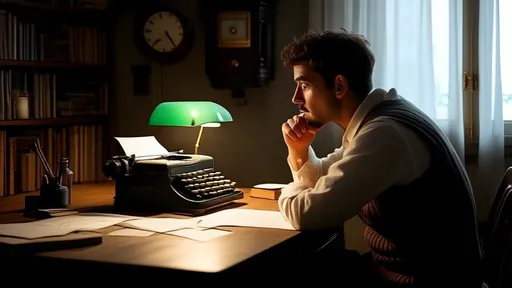

Beyond the sound itself, vinyl advocates point to the ritual. Playing a record is an intentional act. It involves selecting an album, carefully removing the disc from its sleeve, cleaning it, and placing it on the platter. It demands engagement. You cannot skip tracks with a casual click; you listen to an album as the artist intended, side A and then side B. This physical, deliberate process creates a deeper connection to the music. The large-format artwork, the liner notes, the very object itself—all contribute to a more holistic and appreciative listening experience. It is music you not only hear but also hold.

The digital argument, in stark contrast, is built on the unassailable pillars of precision and purity. Digital audio, in its fundamental form, is a representation of the analog wave measured in tiny fragments—44,100 times per second in the case of CD-quality audio. Each fragment is assigned a precise numerical value. The defense of digital hinges on the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, a mathematical proof stating that a signal can be perfectly reconstructed if it is sampled at a rate more than twice its highest frequency. Since human hearing tops out at around 20 kHz, a 44.1 kHz sampling rate is more than sufficient to capture everything we can perceive.

Therefore, from a technical standpoint, a high-resolution digital file (e.g., 24-bit/96kHz or higher) is a perfect, or indeed a flawless, archival copy of the original master recording. It is immune to the degradation, noise, and physical imperfections inherent to vinyl. There is no wow, no flutter, no surface noise, no gradual wear from a diamond needle grinding against plastic. The dynamic range is vastly superior, allowing for both whisper-quiet passages and explosive crescendos without distortion. The sound is clean, precise, and perfectly transparent. For its champions, digital is the ultimate fidelity—the unvarnished truth of the recording, delivered without coloration or added noise.

Yet, this is where the debate transcends mere specifications and enters the realm of human perception. The "perfect" sound of digital is often critiqued as being sterile, cold, or harsh, particularly in early CD masters that were poorly remastered from analog tapes with excessive compression. This has led to the phenomenon of the "loudness war," where dynamics are sacrificed for perceived volume, an issue unrelated to the digital format itself but often blamed on it. The very perfection that defines digital can be its Achilles' heel in the listening experience; some find its clinical accuracy lacking in the soul and character they crave.

Psychoacoustics and confirmation bias play enormous roles in this perception. If a listener has invested thousands of dollars in a high-end turntable, cartridge, and amplifier, they are psychologically primed to believe it sounds better. The ritual of playing the record, the tactile feedback, the visual of the spinning disc—all these elements prime the brain to enjoy the music more. It is a more engaging multi-sensory experience. Conversely, the convenience of digital—streaming millions of songs instantly—can subconsciously devalue the music, making it background noise rather than an event. The format itself can change how we listen, which in turn changes how we hear.

Perhaps the most logical conclusion is that the pursuit of a definitive answer is a fool's errand. The notion of "better" is fundamentally subjective. It is not a scientific standard but a personal preference shaped by taste, experience, and psychology. For some, the warmth and ritual of vinyl provide a more authentic and enjoyable connection to music. For others, the crystal-clear accuracy and immense convenience of digital are unbeatable. The master recording, the quality of the pressings or the digital encoding, and the entire playback chain—from the stylus or DAC to the speakers and the room's acoustics—are all far more significant variables than the format itself.

In the end, the vinyl versus digital debate is not a technical problem to be solved but a testament to the beautiful complexity of our relationship with music. It is not about the data; it is about the feeling. The debate endures not because we lack answers, but because the question itself is so deeply personal. It asks not what is objectively true, but what moves us. And that is an answer that will always be found not in a specification sheet, but in the quiet, personal space between the listener's ears and the music they love.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025