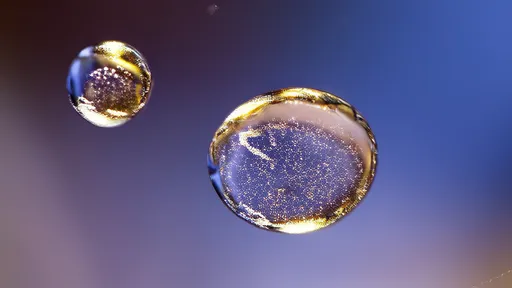

The concept of quantum superposition has long fascinated physicists, philosophers, and even poets. It suggests that particles can exist in multiple states simultaneously until observed—a paradox that defies classical logic. But what if this principle extends beyond the realm of subatomic particles? What if love, that most human of emotions, operates under similar rules? The idea of love and non-love coexisting in a quantum-like state is not just a metaphor; it’s a lens through which we can examine the contradictions of the heart.

Love is often portrayed as binary: you either love someone or you don’t. Yet anyone who has experienced the complexity of relationships knows this to be a simplification. Emotions are rarely so tidy. The heart doesn’t toggle between on and off; it flickers, fluctuates, and sometimes holds opposing feelings in tandem. This is where the analogy to quantum mechanics becomes startlingly apt. Just as an electron can be both particle and wave, love can be both present and absent, depending on how—and when—it is observed.

Consider the aftermath of a breakup. One moment, you’re certain you’ve moved on; the next, a memory ambushes you, and the love you thought was dead resurfaces. This isn’t inconsistency—it’s superposition. The love exists in a state of potential, collapsing into definiteness only when confronted by a specific context or trigger. The past and present emotions don’t cancel each other out; they coexist, unresolved, until measured by the act of reflection.

This framework also sheds light on the phenomenon of ambivalence. How often have we heard someone say, “I love them, but I’m not in love with them”? Such statements are often dismissed as indecision, but they might instead reflect a genuine quantum-like duality. The love is there, and so is its absence. The contradiction isn’t a failure of feeling but evidence of its complexity. In this sense, the heart is less like a switch and more like a quantum bit—capable of holding multiple states at once.

Even in the earliest stages of attraction, superposition plays a role. The flutter of excitement when meeting someone new is often accompanied by a parallel uncertainty: Could this be something? Or nothing? Until the moment of commitment—or rejection—the relationship exists in a haze of possibilities. This is the romantic equivalent of Schrödinger’s cat, alive and dead until the box is opened. The difference, of course, is that human emotions are far messier than theoretical felines.

The implications extend beyond individual relationships. Cultural narratives around love—the idea of “the one,” the expectation of eternal passion—often fail to accommodate its quantum nature. We’re taught to seek clarity, to demand certainty. But what if the healthiest relationships are those that embrace superposition? What if love isn’t meant to be pinned down, but rather allowed to oscillate, to exist in a spectrum of states?

Science, too, is beginning to explore the overlap between quantum principles and cognitive processes. Some researchers suggest that the brain might employ quantum-like mechanisms in decision-making and emotion. If true, it would mean that the superposition of love and non-love isn’t just poetic—it’s biological. The heart’s contradictions could be wired into the very fabric of our minds.

None of this is to say that love is merely a quantum algorithm. The analogy is a tool, not a theory. But it offers a way to reconcile the heart’s paradoxes without reducing them to pathology. Love doesn’t have to be all or nothing. It can be both. It can be neither. It can hover in the in-between, defying measurement, until the moment it doesn’t. And perhaps that’s the most human thing of all.

In the end, the quantum view of love doesn’t simplify matters. If anything, it complicates them. But it also validates what many have felt instinctively: that love is not a fixed point, but a probability cloud—a shimmering, shifting thing that resists easy definition. To love is to exist in superposition, and that, in itself, is a kind of magic.

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025